The Vedic tradition views the journey ( yāna ) of the individual after death as a passage from one plane of being ( loka ) to another; and although there is the possibility of perpetuity ( stāyitā ) on a given plane until the End of Time ( kalpānta , Mahā-pralaya ), there is no conception of the possibility of a return to a past state. The later doctrine of reincarnation, in which the possibility of a return to a previous state is conceived, seems to reflect an edifying trend of religious ( bhakti-vāda ) and psychological ( hīnayāna ) extensions, perhaps incorporating non-Vedic folk elements . [1]

More properly, two different paths can be followed: the angelic path ( devayāna ) in the case of the individual whose vessel is knowledge, and the patriarchal path ( pitṛyāna ) in the case of one whose vessel is work ( karma ) performed for reward. In the former case, the individual passes through the ‘Sun’ and beyond to the Supreme Self and the Bottomless; in the latter, he reaches only the ‘Moon’ and, in due course, returns to a new bodily state in a later sub-time ( manvantara ), when the choice of the path presents itself again. What follows, however, does not take into account this distinction of ways, but rather the distinction between those who, on the one hand, are carried either by the understanding or by works, being equally travelers, and those, on the other hand, who, having neither understood nor yet worked, the Last Judgment finds them not only without annihilation, but also without merit.

In any case, the final goal of the journey is on the Fatherly Shore of the Sea of Life ( saṃsāra ). When the landing takes place there, the Jīvātma knows himself as Paramātman , the absolute-space-in-the-heart ( antarhṛdaya ākāśa ) is known as the absolute body-space ( ākāśa-śarīra ) of Being and Non-being, and the Sea of Life is as it were counter-visible ( paryapaśyata ) by the Self as the multiplicity of its own Identity [2] . In the journey we are given indications of Paradise ( prāṇārāma , nandana ), in the Union ( sāyujya samādhi ) which consumes thought ( dhyāna ), in the Bliss ( ānanda ) which consumes Will ( kāma ), and in the consent ( sāhitya ) of Art ( nirmāṇa ): knowledge, love and work becoming pure Act ( asakta ).

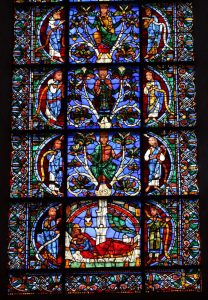

But if the possibility of a Gradual Emancipation ( krama-mukti ) is open to the Wanderer [3] , it is also possible for one whose ship is rudderless, or misdirected, to wander over unknown waters towards an unknown land, farther and farther from the Quay ( ghāṭ ): so far and so long that he may no longer be in sight of the Unknown Shore when every shore and every ship is dissolved at the End of Time. Thus, at the End of Time, there is a departure for those who are liberated ( mukta ) and bound to the Ego ( māna-baddhaka ). In the Christian tradition, this is called the Last Judgment.

Except for the highest Devas, the Angels (ājānaja ), whose being is Eternity, all beings, whether ‘living or dead’, are ‘judged’ in this Last Day. The Self of those who have already attained complete Realization ( mukti ) ( nirguṇa ) is already in full conscious identity with the Supreme Identity; and now, for those whose Realization has been “by degrees” ( krama ) or qualified ( saguṇa ), there follows the last death of the categorical Ego, a “death” which is absolutely Mors janua vitae , an emancipation from all possible contingency, the Gates of Heaven open to the Jīvātman , become Kṛtātman, “perfect Self”, so that it becomes again ( abhisambhavati ) in its own form ( sva-rūpa ), without imagination ( nirābhāsa ), pure consciousness ( cit ) and unmixed delight ( pūrṇānanda ).^

But for those lost beings who have not attained in Time even a partial realization, but who are still totally involved in the net of illusion ( moha-kalila ), considering that the Ego is the Self, for them there can be no present possibility of emancipation at the End of Time: having thought, still thinking that to act “for the good of the Self” ( Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, II, 4, 5) means nothing else than to satisfy all the desires of the Ego, by serving the body here and now, living according to such an ” Asura Upaniṣad “, as this one, these will ” perish ” ( Chāndogya Upaniṣad , VIII, 8). These are the ” damned “. Their damnation is a personal condemnation of the self and the Self to an endless, but not eternal, latency, to a relative, but not absolute annihilation; to a hell under the silent and icy sea of non-Time ( kalpāntara ) which separates Time from Time, there, by the necessity of “the Justice of God”, to await their mortal return in another Time ( kalpa ), where the possibility of realizing or not an immediate or deferred emancipation will present itself again.

Abhimānatva [4] is thus the “original sin.” Satan’s claim to “equality with God,” the assertion of the independence and persistence of the Ego, which is the occasion of his fall and that of those who follow him. The fall of man, which is of the same nature, has been traditionally described as the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Life, planted by the Self itself, by God, in the Garden of Life ( prāṇārāma ), as a thing beautiful and a delight to the eyes, for His pleasure and that of man. But eating of the fruit is a mortal sin ( anṛta ) against the Spirit, “forbidden” to man as an individual ego [5] ; for “eating” is an assimilation and self-identification with things “as they are in themselves”, and not “as they are in God”, hence an absorption of that which is nothing in itself, a venom ( viṣa ) [6] which is Death from the point of view of Eternal Life, a closing of the Gates of Paradise.

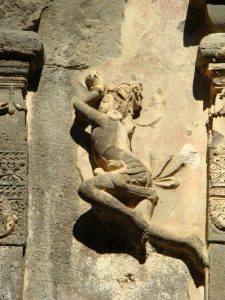

None but the Self can swallow such venom and yet live, as Śiva does when, by another image, the dvandva ‘s scourge [7] occurred at the churning of the sea of milk; the wound and signature of this scourge being the blue-black stain on his throat as Nīlakaṇṭha, Viṣakaṇṭha, Viṣāgipā, his grasping of the serpent on his chest as nāga-yajñopavīta, and his “addiction” to drugs. This apparent surrender of the Self to the tragedy ( anṛta , arta ) of Life, this accepted pain, is the Passion of God and of every man [8] .

[1] See Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Yaksas , I, p.14, note 1.

[2] Pañcaviṃśa Brāhmaṇa , VII, 8, 1; Śaṅkarācārya, Svātmanirūpaṇa , 95, “On the vast canvas of the Self, the picture of the many worlds is painted by the Self itself, and this supreme Self takes great pleasure in it.”

[3] The concepts yāna and Krama-mukti imply the hypothesis of a crossing of the sea of life ( saṃsāra ). If the Upaniṣads also envisage the possibility of an Immediate Liberation and a consequent Transformation ( abhisambhava or parāvṛtti ), the realization, “I am Brahman”, “You are That” in concrete experience, this dissolution of the knots of the heart in a single gesture is not our purpose.

[4] [“Pride”] (NdT)

[5] It must not be thought that the fact that man is represented as yielding to the seduction of woman implies a purely carnal fall. Here, “man” means “subject” and “woman” means “object” (as pratīka , in each case); the fall is equally a derogation of the Intellect and the Will.

[6] It is impossible not to see a connection between viṣa “poison”, and viṣayatā , objectivity; cf. Maitrī Upaniṣad, VI, 31, where vision is said to “feed” on the apsaras (i.e. the fascinating possibilities of being) as objects of the senses ( viṣayān ); also Nirukta , V, 15, where apsaras is artificially connected to a-psā , giving the meaning of “forbidden food”; Bṛhaddevatā , V, 148 and 149, and Sarvānukramaṇī , I, 166, where Mitra-Varunā are seduced by the sight of Urvaśī.

[7] [“Duality”] (NdT)

[8] “That heart which keeps itself aloof from pain and misfortune, no seal or signature of love can know it” (Sanā, I).